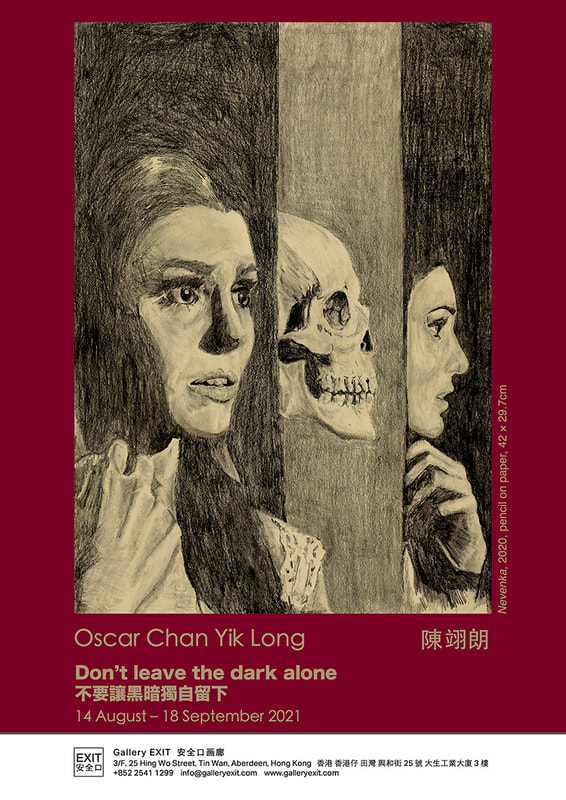

Don't leave the dark alone | 不要讓黑暗獨自留下

|

Oscar Chan Yik Long: Don’t leave the dark alone

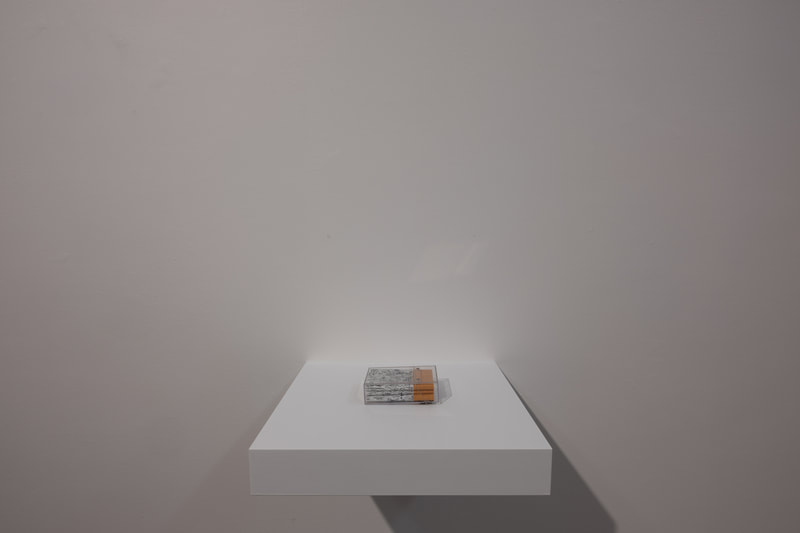

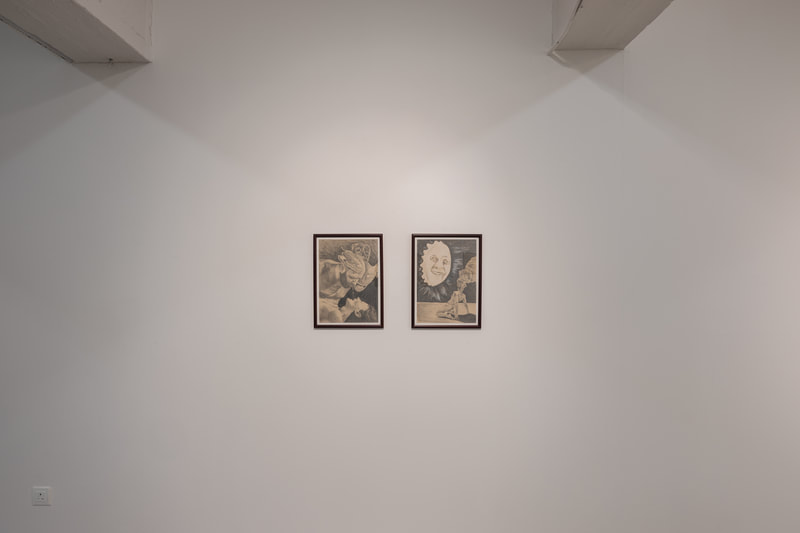

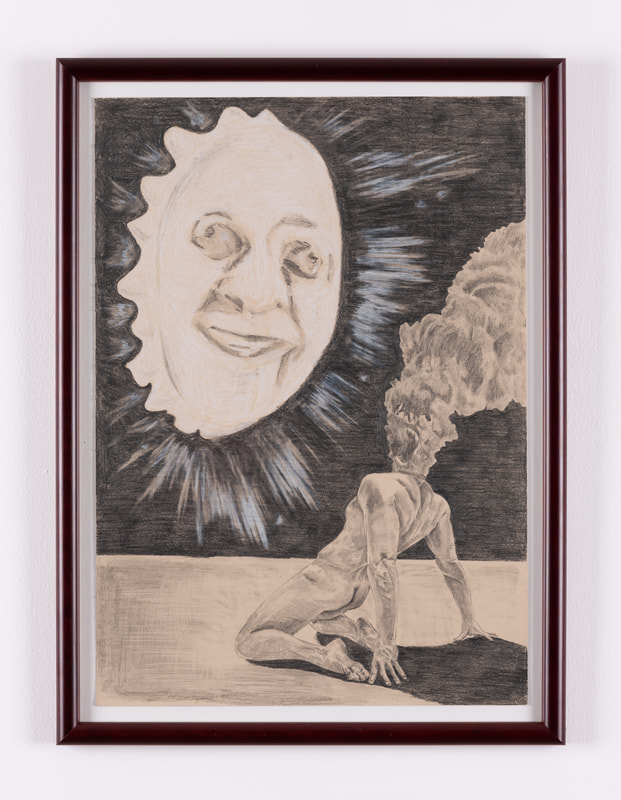

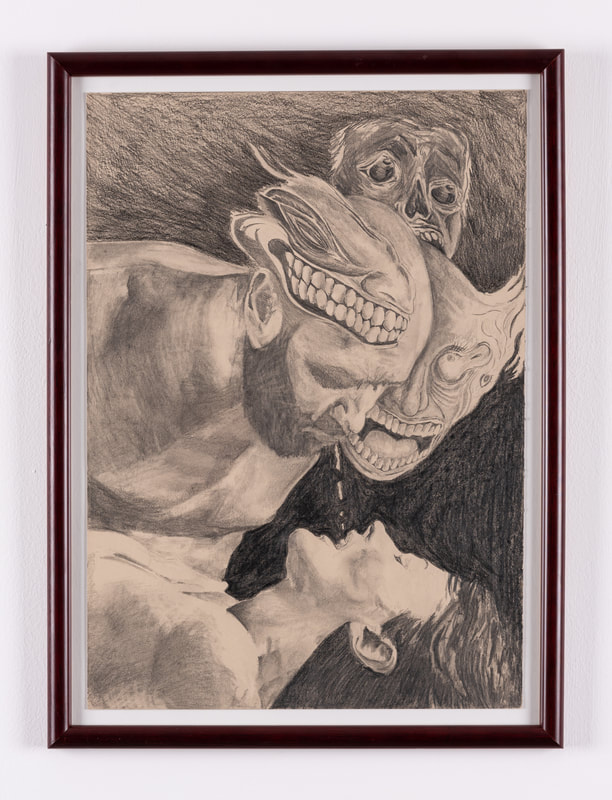

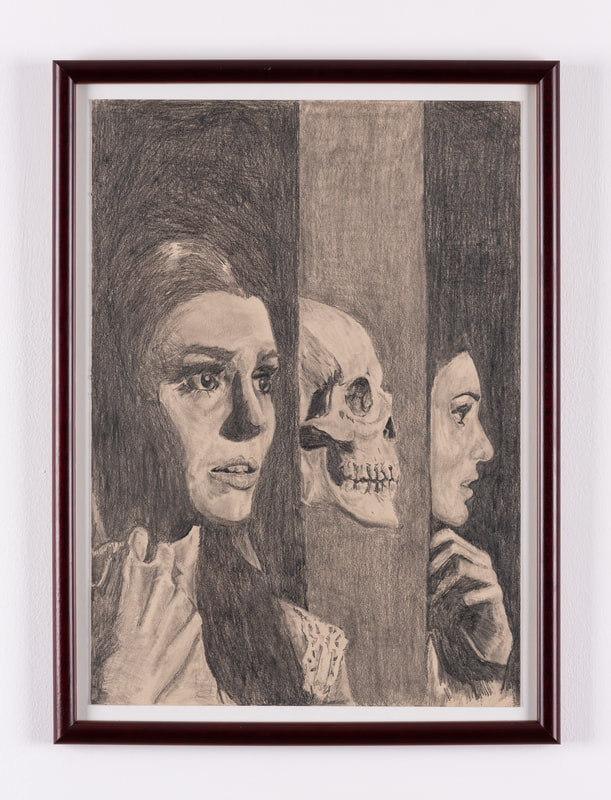

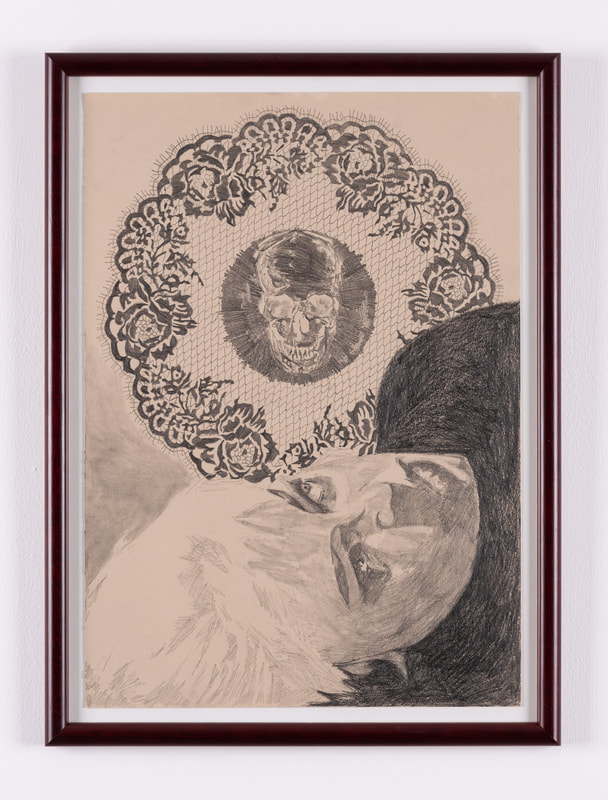

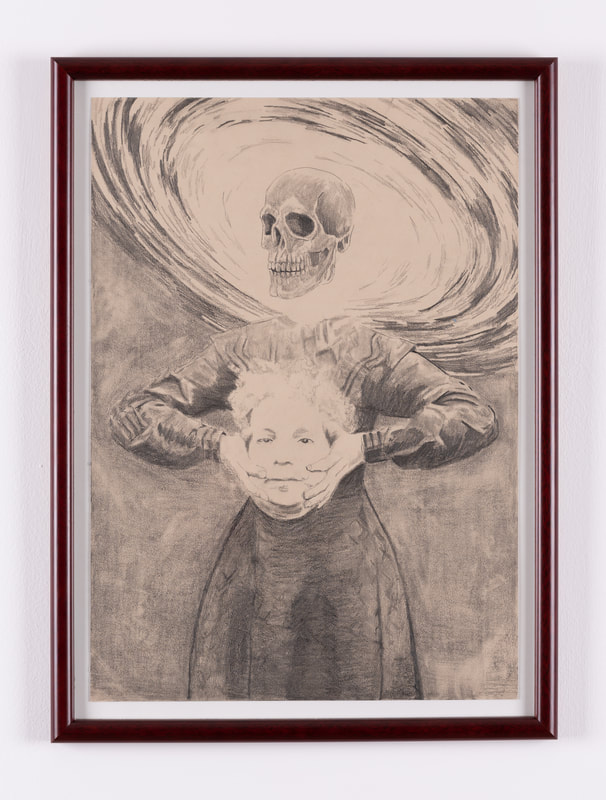

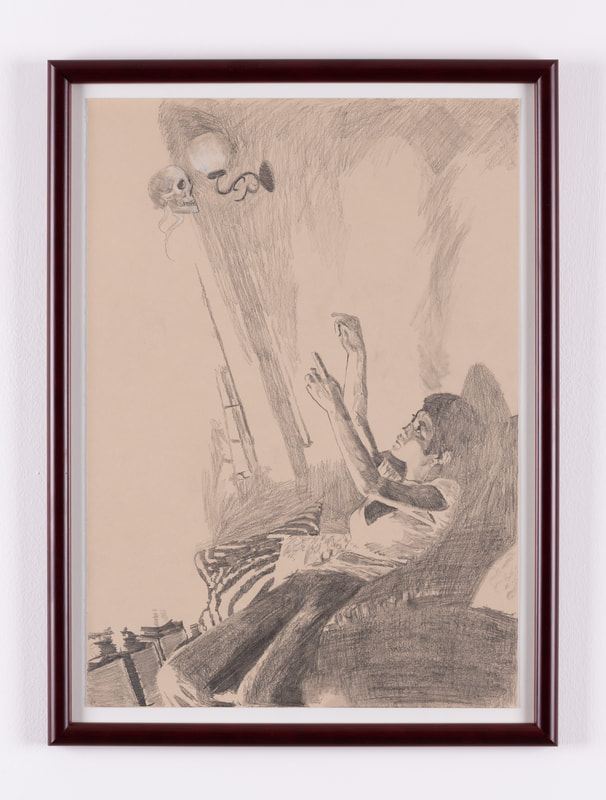

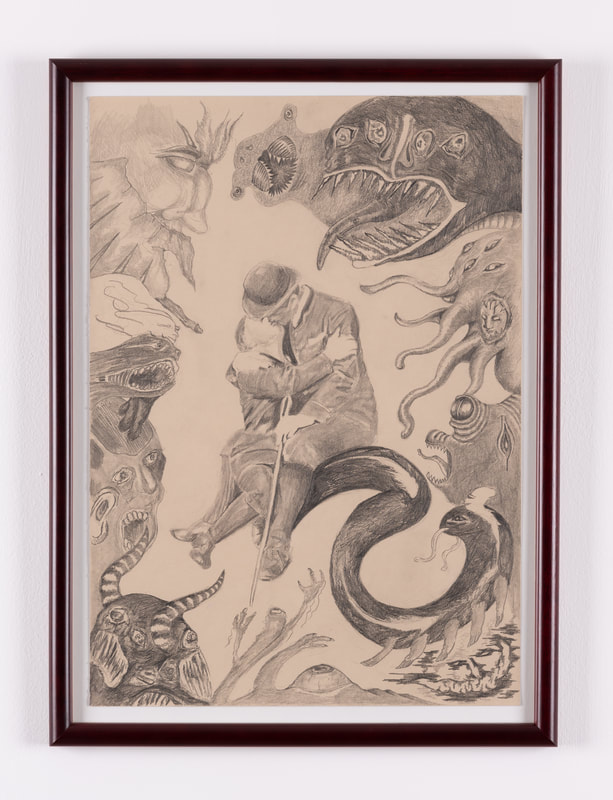

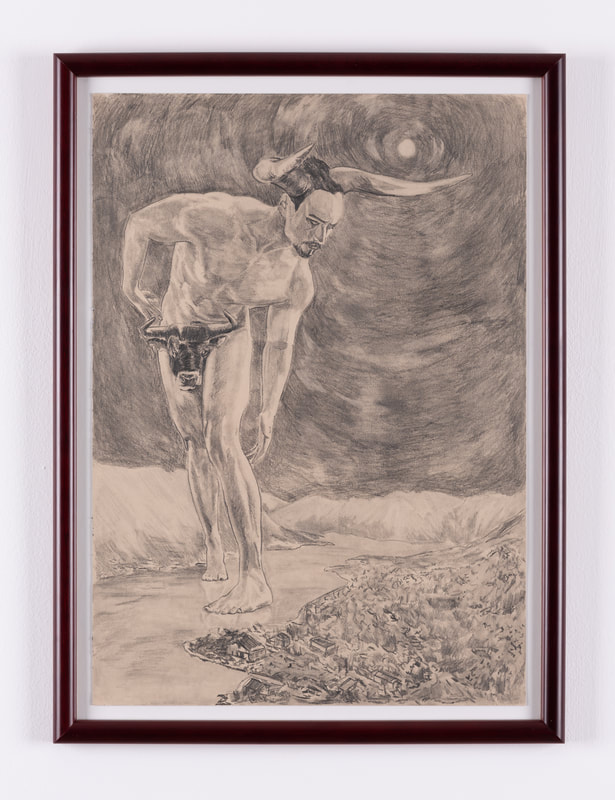

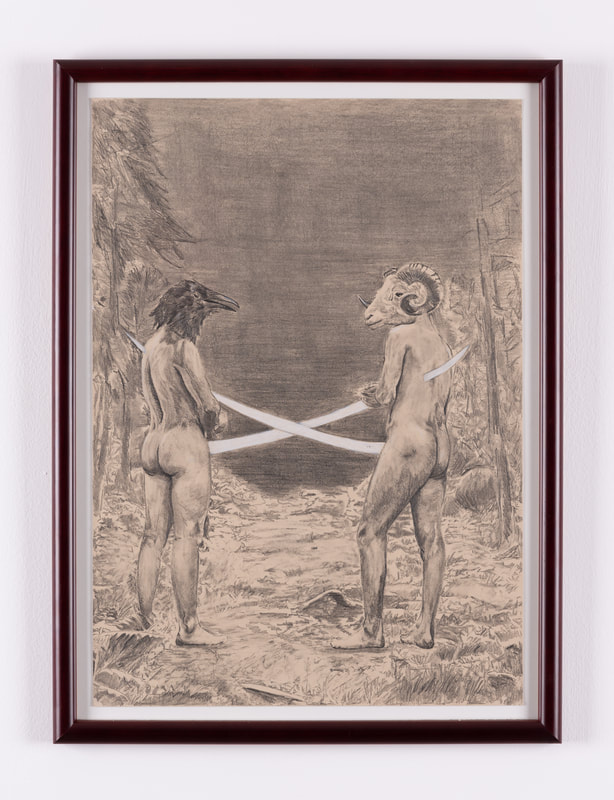

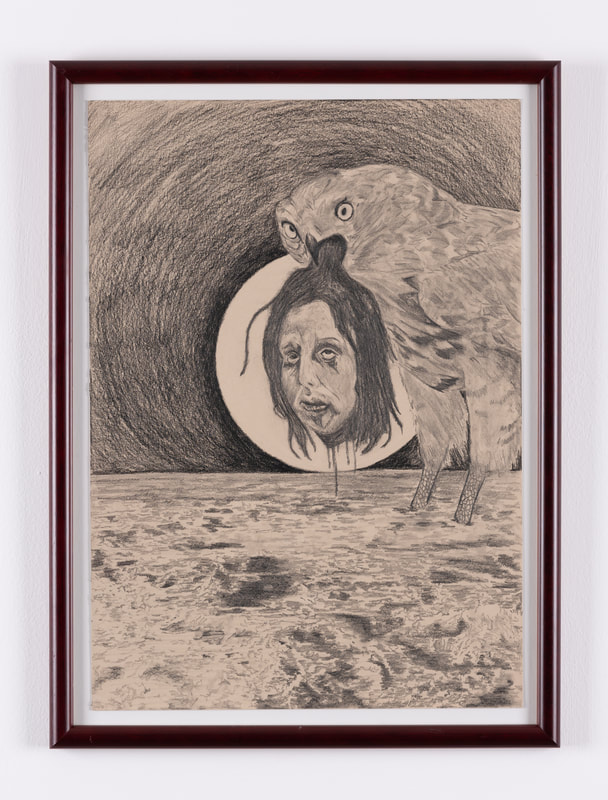

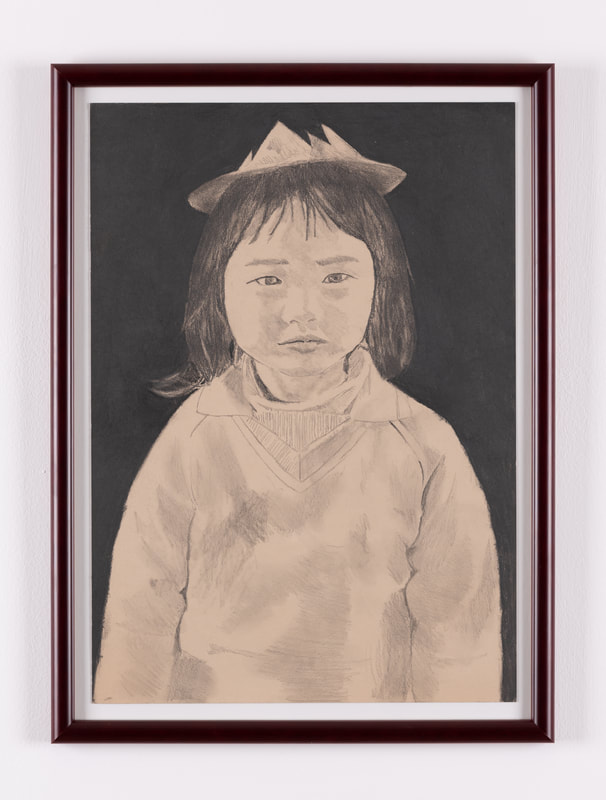

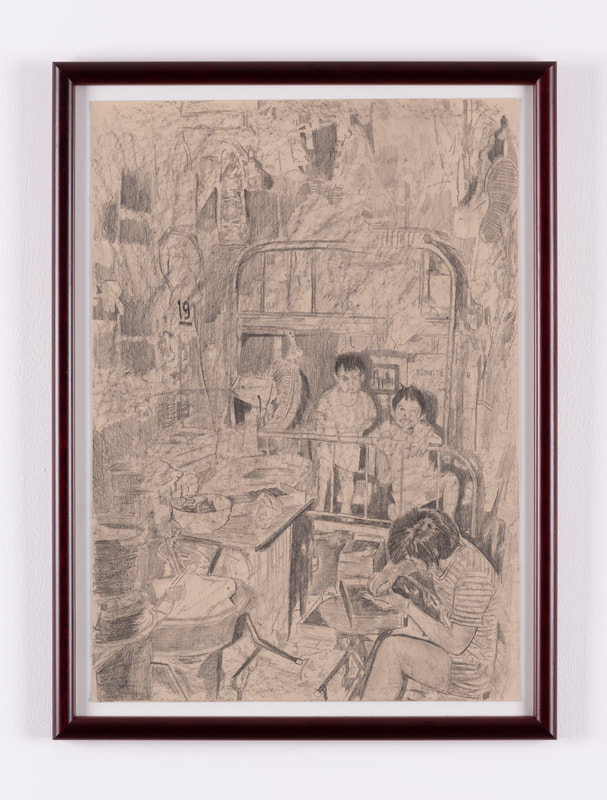

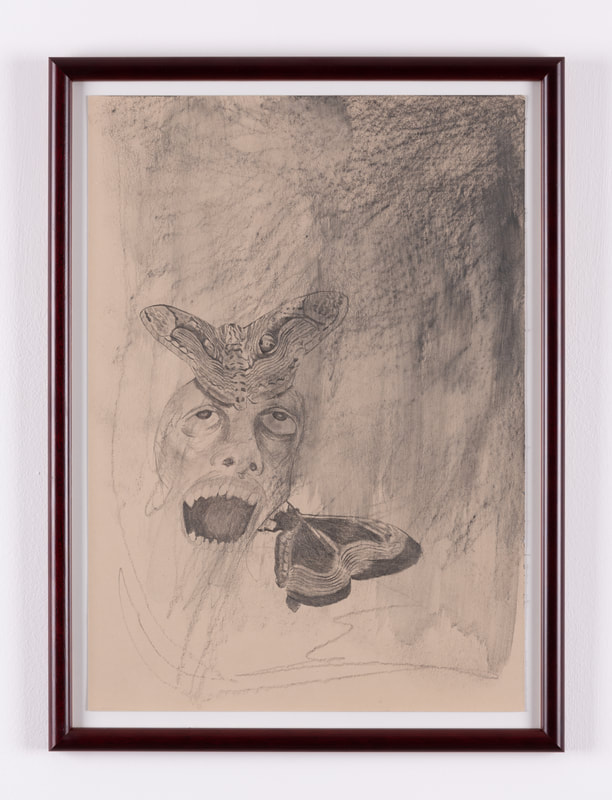

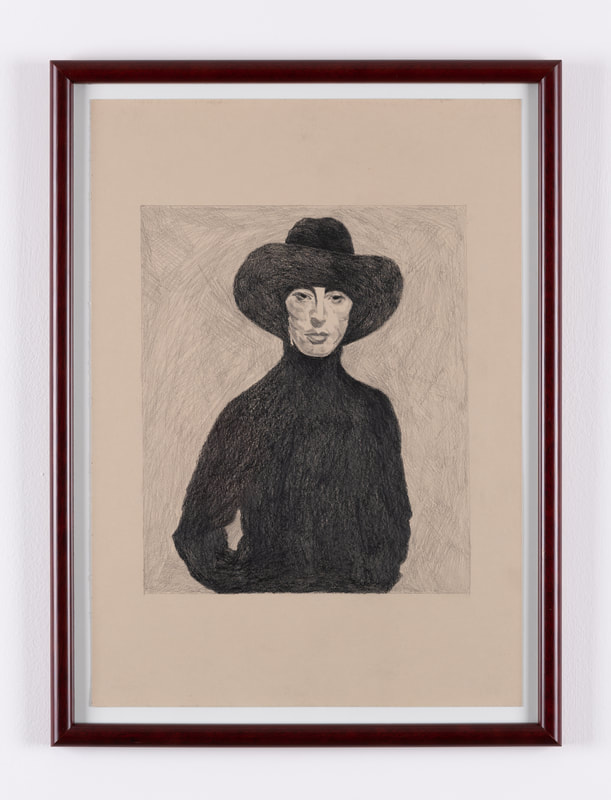

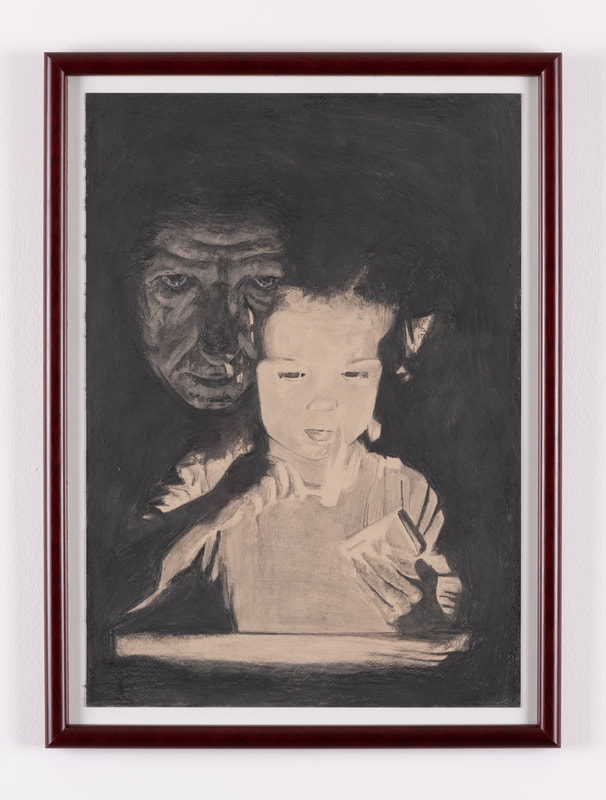

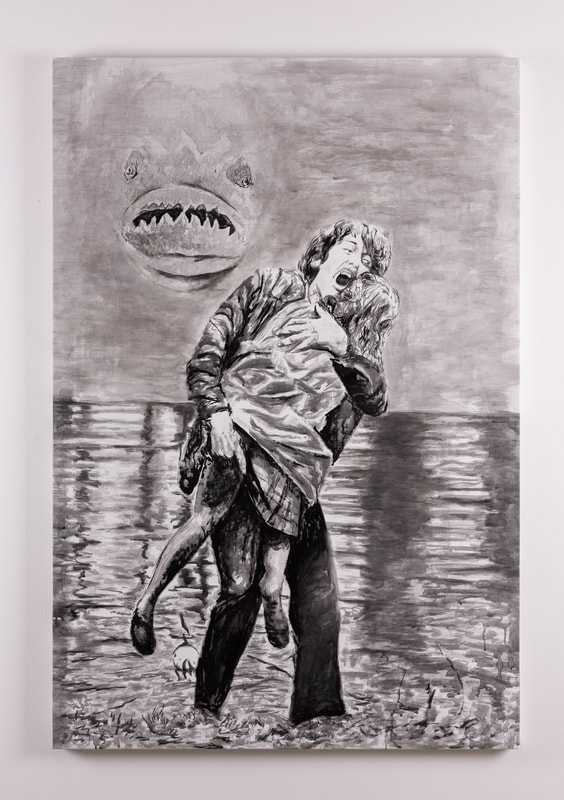

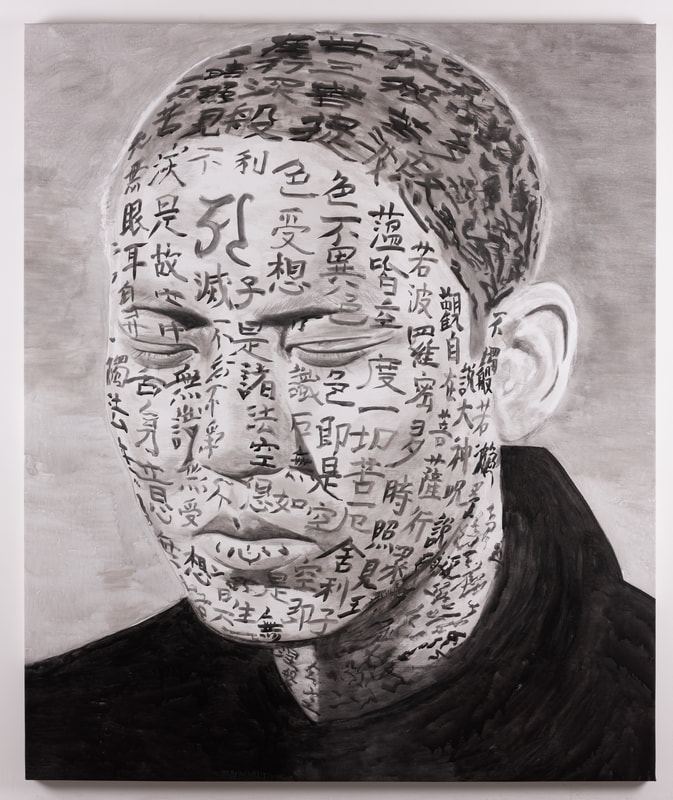

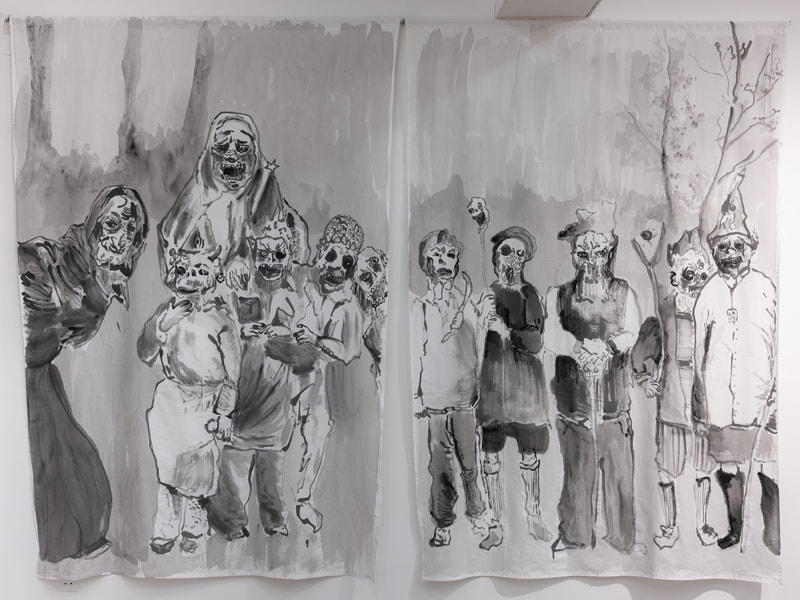

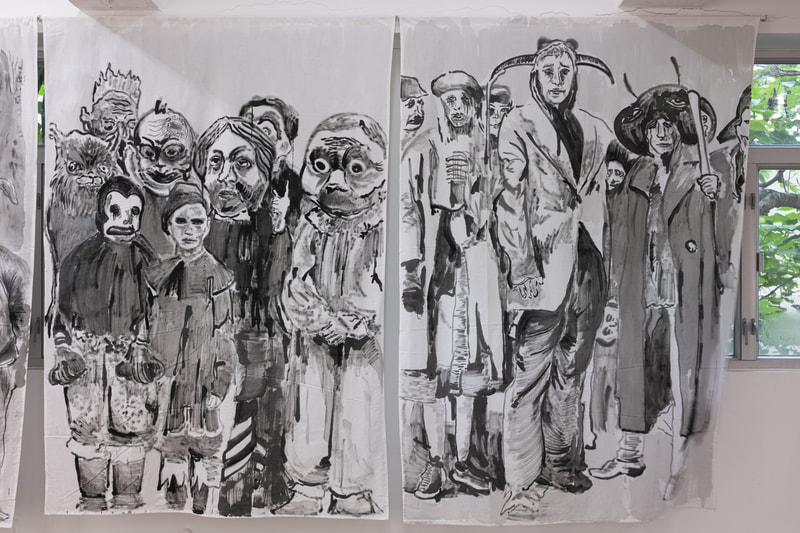

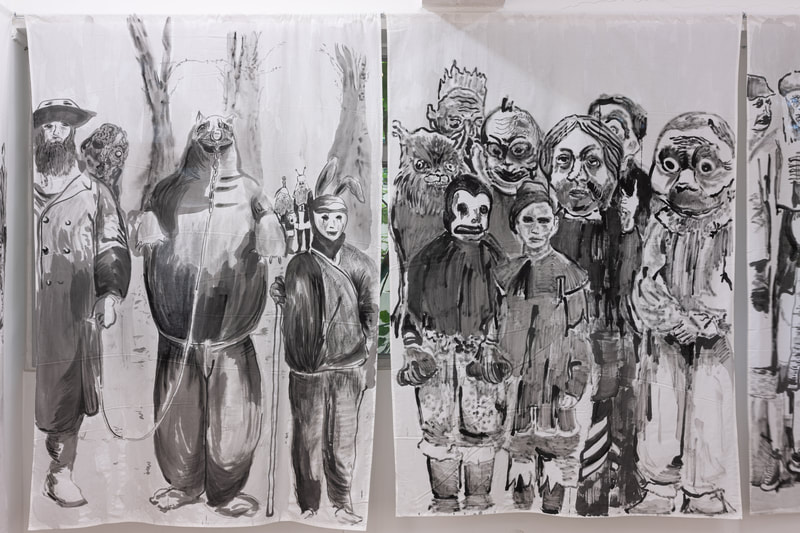

14 August – 18 September 2021 Opening: Saturday, 14 September 2021, 2–5 pm Venue: Gallery EXIT, 3/F, 25 Hing Wo Street, Tin Wan, Aberdeen, Hong Kong Opening Hours: Tue–Sat, 11 am – 6 pm Gallery EXIT is pleased to present its first solo exhibition by Oscar Chan Yik Long, titled ‘Don’t leave the dark alone’. The exhibition will open on 14 August and remain on view through 18 September. An opening reception will be held on Saturday, 14 August at 2–5 pm. The works in Chan’s exhibition share some characteristics. They are black-and-white, figurative and reference both Oriental myths and Occidental art, but mainly twentieth-century cinema from all over the world. Yet none of this should deter viewers from approaching each work by Chan as an individual entity: a window into a parallel reality, a mirror reflecting its environment or just a surface revealing itself. ‘Don’t leave the dark alone’ is a phrase taken out of its original context (something to do with managing laundry) and redeployed for managing darkness itself, or at least the fear of darkness and the anxiety or damage it may cause. Used as an exhibition title, the phrase gives us license to equate artistic strategies employing a metaphorical darkness (ink, graphite) with the real thing (how we respond to the dark outside and inside). The exhibition is set up both to encourage and discourage such ‘unreflective’ understanding by offering a variety of surfaces for reflection. It opens with four paintings in ink on stretched canvas, continues with ambiguous use-objects – ink drawings turned into a manufactured rug or executed on cigarettes emptied of their intoxicating content, painted curtains meant to be back-lit by the sun – and ends with a longer series of glazed and framed drawings in graphite on not-quite-white paper. The four paintings that open the exhibition are all from 2021 and based on film frames representing different traditions or schools of 1960s and ’70s cinema: psychological entertainment, social critique and mythological parables by American, British, German and Japanese authors. The finished works reflect individual and societal tensions experienced and understood by cinema goers in the past, but Chan’s translation of cinema into painting also introduces alterations and additions that speak to the fears and worries of the present age and our attempts at overcoming them. How do we know if the dead would not regret their efforts to survive? is a circular woollen rug. Woven after a densely dramatic ink drawing by Chan, it features some of the monstrous and ‘pessimistic’ visual elements viewers have come to expect from him. The title is a quote from The Adjustment of Controversies by Zhuangzi, the fourth-century BC philosopher who favoured dialogue as a format for ventilating controversial and irresolvable issues – arguably an ‘optimistic’ stance. Although the phrase expresses disenchantment with life as it is lived, Zhuangzi uses it to discuss the difficulties of ‘harmonising of conflicting opinions’ when no authoritative truth can be relied upon to accept or reject them. The Most Misplaced Worry (2018/20) is a transparent plastic box filled with the empty shells of 20 Marlboro cigarettes. Chan appropriated them from someone who, he thought, wasn’t supposed to smoke them. With a fine-tipped pen he applied floating, disembodied elements from his drawing repertoire – toothy grins, staring eyes, hair standing on end – onto the thin white cigarette papers before removing all their tobacco content. The eight painted cotton curtains titled 120 Judge John Aiso Street were made for a group exhibition in France in 2020, where they covered as many windows. The work stages a sensation of watching a ragtag patrol of undead creatures surrounding the exhibition space. The title is the address of the church assaulted by a similarly menacing crowd in John Carpenter’s 1987 horror film Prince of Darkness, and some of the imagery was lifted from the same source, but there are also filtered influences from classical painters like Francisco Goya or James Ensor. The aesthetic and psychological effects are similar to those Chan achieved elsewhere, notably in his murals, with visual quotes from East Asian mythology and ghost stories. The concluding segment of ‘Don’t leave the dark alone’ is a series of 16 drawings, individually titled and installed in smaller groups. Chan’s visual meditations are based on imagery borrowed or paraphrased from a variety of sources – notably horror movies, old postcards and late-nineteenth-century European graphic art – and form a library of his references and interests in 2020 and early 2021. This was the time of the Parisian confinement and of second-wave Covid-19 restrictions in Helsinki, where he spent time as an artist-in-residence last winter to prepare his participation (with a site-specific mural and another circular woollen rug) in the group exhibition ‘First International Festival of Manuports’ at Kunsthalle Kohta. In these drawings, Chan occasionally washes an area of intensely applied graphite over with turpentine, or uses white highlights to remind us that his paper is toned. We never know for sure when an artist’s black should be read as the symbolic counterpart to his white. Sometimes they have no poetic charge but are mere surfaces revealing nothing but themselves. The artist is not obliged to resolve such ambiguities in his drawings or paintings, nor to ‘harmonise’ any conflicts of interpretation that his work may get embroiled in, but he also cannot prevent it from being understood metaphorically, as symbol and allegory. The alternative is, as so often, worse. Imagine that what you see on these gallery walls could only be understood literally, and that the only appropriate reaction to ‘frightening’ imagery would be to actually become afraid, to renounce everything dark and dangerous for fear of hurting yourself or others. When Oscar Chan Yik Long urges us not to leave the dark alone, he also urges us not to part ways with the pleasure we may wish to take from darkness in its refined forms. |

陳翊朗:不要讓黑暗獨自留下

2021年8月14日至9月18日 開幕酒會:2021年8月14日星期六,下午2時至5時 地點:香港香港仔田灣興和街25號大生工業大廈3樓安全口畫廊 開放時間:星期二至六上午11時至下午6時 安全口畫廊很高興呈獻陳翊朗首次個展《不要讓黑暗獨自留下》,展期為8月14日至9月18日。開幕酒會將於8月14日星期六下午2時至5時舉行。 是次展出作品都有一些共通點:它們全是黑白色調、具象且指涉了東方神話及歐陸藝術,主要為來自世界各地的二十世紀電影。然而觀眾仍可以視陳氏的每件作品為單獨的實體:作為一扇通往另一個平行世界的窗口、一面反映周圍環境的鏡子,又或只是一個揭示自身的表面。 展覽標題將「不要讓黑暗獨自留下」從其原本的語境(跟洗衣服有關)抽離,重新用以對應黑暗本身,或至少是對黑暗的恐懼以及它可能造成的焦慮或傷害。作為展覽標題,這句話讓我們能夠隨意將隱喻黑暗的藝術策略(墨、石墨)與真實的事物(我們如何回應內外的黑暗)兩者作出類比。 是次展覽旨在提供各種帶來反射/思的表面,同時鼓勵及阻止這種「非反射/思性」的理解。展覽以四幅畫布上的墨水畫作開場,伴隨而來是意義曖昧的物件——給製造成地毯或繪製在掏空了醉人內容的香煙上的水墨畫、讓陽光從後方穿透的彩繪窗簾——並以一個較長的、以石墨於並不完全白色的紙張上繪製、釉面或連框的素描系列作結。 為展覽揭開序幕的四幅畫作均於2021年創作,取材於上世紀六十及七十年代的代表傳統或流派的電影畫面:美國、英國、德國和日本創作者筆下的心理娛樂、社會批判,以及神話寓言。作品反映了昔日電影觀眾曾經體會了解的個體與社會的張力,而陳氏將電影轉化為繪畫的同時亦引入了改動及添加,回應當代的恐懼與憂慮,以及我們將之克服的嘗試。 《予惡乎知夫死者不悔其始之蘄生乎?》是一幅圓形的羊毛地毯。地毯以陳氏綿密而戲劇性的水墨畫編織而成,包含了觀眾在他的作品中屢見不鮮的怪異及「悲觀」的視覺元素。作品標題引用了公元前四世紀的哲學家莊子的《齊物論》。莊子偏好使用對話作為一種宣洩爭議性及無法解決的問題的形式——可以說是一種「樂觀」的立場。雖然這句話表達了對活著的生命的失望,莊子卻以它來討論當沒有權威的真理可以依靠時「協調矛盾意見」的困難。 《最錯置的擔憂》(2018/20年)是一只裝載了二十根萬寶路香煙空殼的透明塑膠箱子。陳氏從某個他認為不應該抽煙的人那裏挪用了香煙。他以一支尖細的筆,把他繪畫作品中飄浮的、斷裂的元素——咧嘴而笑、瞪目而視、毛管直豎——置於薄薄的白色捲煙紙上,再把內裏的煙草掏空。 《120 Judge John Aiso Street》的八面彩繪棉布簾子乃藝術家為2020年在法國的一次群展製作而成,用以覆蓋八面窗戶。作品營造了一種觀看圍繞展覽空間四出巡邏的襤褸喪屍隊列的感覺。作品標題為約翰·卡本特(John Carpenter)的恐怖電影《沉睡百萬年》(Prince of Darkness ,1987年)中被同樣來勢洶洶的人群襲擊的教堂的地址,部分圖像摘取自同一電影,亦滲入了古典畫家如法蘭西斯科·哥雅(Francisco Goya)和詹姆斯・恩索(James Ensor)的影響。這些美學及心理效果近似陳氏在別的作品中所表達的,尤見於他帶有源自東亞神話及鬼故事的視覺引用的壁畫作品。 展覽終章部分為一系列十六幅素描作品,各有獨立標題並分成小組裝置。陳氏的視覺冥想建基於從各種來源——特別是恐怖電影、古老明信片和十九世紀後期的歐洲圖像藝術——借用或改編的圖像;這些圖像在2020年至2021年初成為他的參考及興趣資料庫。那時正值巴黎封鎖以及赫爾辛基第二波新冠肺炎限制,去年冬天陳氏曾在後者作駐場藝術家,以(一場域特定壁畫及另一幅羊毛地毯)準備參加於Kunsthalle Kohta舉行的群展「First International Festival of Manuports」。 在這些素描裏,陳氏偶爾會以松節油清洗畫面上一片塗滿石墨的地方,或以白色高光來提醒我們紙張是有色調的。我們永遠不會知道甚麼時候藝術家的黑應該被解讀為白的相反象徵。有些時候它們並沒有詩意,而只是純粹的表面,除了顯示自身以外就再沒有別的東西。藝術家沒有義務去解決他的素描或繪畫中的這些歧義,也沒有義務去「協調」他的作品可能捲入的任何解釋的矛盾,但亦不能阻止作品被隱喻地理解為象徵及寓言。 然而另一種選擇通常不會好得哪裏去。試想像你在畫廊的這些牆上看到的東西只能從字面上理解,對「恐怖」圖像唯一的恰當反應是真的變得恐懼,因為害怕傷害自己或他人而謝絕一切黑暗及危險的東西。陳翊朗敦促我們不要讓黑暗獨自留下,也不要與我們或可從黑暗更完善的形式中獲得的快樂割席。 |